DAVENPORT

BLUES

DAVENPORT

BLUES

DAVENPORT

BLUES

DAVENPORT

BLUES

Davenport Blues was the first

composition

by Bix Beiderbecke to have been recorded. The historic event took place

in the Gennett Recording Studios of the Starr Piano Company, in

Richmond,

Indiana, on January 26, 1925. Bix wrote, late in December 1924,

to

E. C. A. Wickmeyer of the Starr Piano Co. to arrange a recording

session.

After an exchange of letters, Bix and the contact man of the Starr

Piano

Company settled on Monday, January 26, 1925 as the date for the

recording

session.

The musicians in the group - Bix

Beiderbecke

and His Rhythm Jugglers - were: Bix (cornet), Don Murray (clarinet),

Tommy

Dorsey (trombone), Paul Mertz (piano), Tommy Gargano (drums), and Howdy

Quicksell (banjo). Bix drove with Hoagy Carmichael from Indianapolis

and

the musicians were supposed to meet Bix at the Gennett studios. Howdy

Quicksell

did not make it until the afternoon and therefore did not participate

in

the first two recordings, Toddlin' Blues and Davenport

Blues. All the musicians played in the last two recordings, Magic

Blues and No One Knows What's It All About, but

all

takes of these two songs were destroyed. Murray, Dorsey, Mertz and

Quicksell

were members of the Jean Goldkette Orchestra and we know their

whereabouts

following the Rhythm Jugglers session. Murray, Quicksell and Mertz

continued

working for the Jean Goldkette organization. Nothing is known about Tom

Gargano, a freelance drummer from Detroit. Tommy Dorsey went to New

York

and joined the California Ramblers. Apparently, Tommy Dorsey was good

friends

with Doc Ryker. Rickey Bauchelle, Doc's daughter, has letters that

Tommy

Dorsey wrote to Doc Ryker. In a letter dated February 28, 1925, Tommy

writes,

among other topics, about the Gennett-Jugglers date: "I am sure

surprised

to hear that Bix is going with Charley Straight. I thought he was going

back to school. I hope he dont forget I am living if he gets any

royalty

at all because that trip cost me sixty bucks, they told us in the

Gennett

place that the records would not be out for about two weeks yet."

Excerpt from Randy Sandke's "Bix Beiderbecke:

Watching

a Genius at Work", p. 10-12. To

read about this booklet, click here.

On January 26, 1925 Bix made his

recording debut as a leader. This record would be issued under the name

of Bix Beiderbecke and his Rhythm Jugglers. Bix's nonchalant attitude

towards

this date (and perhaps his career in general) is described by Hoagy

Carmichael

who was present at the session. According to him, the musicians

proceeded

to get drunk to the point that the last two tunes they recorded were

deemed

unacceptable for release. (To be fair, however, the Gennett file card

mentions

technical problems as well.)

Hoagy took photos of the session.

These and a handful of others that show Bix in action (including the

quick

glimpse we get of him in Paul Mertz's home movies of the Goldkette

band,

and the recently discovered newsreel of Bix with Whiteman) all

demonstrate

an attitude towards playing that seems casual in the extreme. Most

trumpet

teachers advocate good posture to facilitate breath control, but Bix is

always seen slouching, or sitting with legs crossed. The recommended

way

to finger a trumpet is with the fingertips straight over the valves,

but

Bix's are bent over in a lazy fashion. Dic Turner, a friend and admirer

of Bix as well as an amateur trumpeter, said Bix played leaning over at

the floor at about a 45 degree angle, and the photos bear this out.

This session will provide much

evidence of Bix's divided attitude towards himself and his music. He is

at the same time dead serious and insouciant to the point of

negligence.

Any good jazz player must find a balance between being focused and

loose,

but with Bix this conflict, combined with his drinking, would later

develop

into a insurmountable problem.

Nevertheless the session did

provide

us with the only example of a jazz tune of Bix's composition:

"Davenport

Blues". Although this tune has at times a "bluesy" feeling, it is again

not a 12-bar blues.

The tune consists of a four bar

introduction, a 16 bar verse followed by a 32 bar chorus, after which

the

the verse and chorus are repeated with a 2 bar extended ending. Two

things

are unusual about this piece. First of all, Bix uses the same melody

for

the verses, but both choruses have have different melodies (though

nearly

identical chords.) Only on the last refrain of the chorus do we hear

the

familiar melody which we identified as "Davenport Blues."

The second unusual feature of

"Davenport

Blues" is the way both choruses end in different chord progressions. In

the first chorus Bix plays breaks over chords reminiscent of a similar

spot in "Jazz Me Blues".

On the second chorus Don Murray

plays the breaks on clarinet over a chord progression more like

"Ostrich

Walk." It is as if Bix couldn't decide which one he liked best. This

indecision

is mentioned by both Bill Challis and Esten Spurrier in regard to Bix's

later piano pieces; Challis: "Each time he'd play a passage he'd think

of some way to improve it," and Spurrier, "He said he'd compose three

bridge

passages but couldn't decide which one to use, and that I had to select

the best."

Carmichael says that "Davenport

Blues" was created on the spot. "Bix stated doodling on his horn.

Finally

he seemed to find a strain that suited him but by that time everybody

had

taken a hand in composing the melody... As far as I could see, they

didn't

have any worked out, or tune for that matter, but when the technician

came

in and gave the high sign, they took off." On the other hand, Paul

Mertz,

the pianist on the date, remembered Bix bringing a lead sheet. The

arrangement

does seem to be too involved for a pick up band to play from memory

with

little rehearsal, especially given their intoxicated state.

Although Bix is often identified

with a penchant for the whole-tone scale, his break in the opening

chorus

is the only recorded example of him actually playing one (tough it's

still

one note shy of a full six-note whole tone scale.) Later on, though,

his

piano pieces would abound in progressions of augmented 9th and 11th

chords

which are derived from whole tone scales.

Since this is Bix's first date

as a leader, it is interesting to consider his choice of sidemen and

tunes.

All the musicians in the band were drawn from Goldkette's working band

(with the exception of Tom Gargano, a freelance drummer from Detroit,

where

the others were based). Bix's had a tendency to contract musicians he

was

currently working with for recording dates. Bix has been criticized for

not going beyond his narrow circle to recruit musicians who were more

on

his level. Yet he undoubtedly felt comfortable in the presence of these

comrades, and in Tommy Dorsey and Don Murray he found very able

support.

He developed a particularly close relationship[ to Don Murray, and Bix

seems to be happiest and most relaxed in the photos of them together.

Don

Murray's premature death in 1929 would be a big personal blow for Bix.

Of the material that Bix chose

to record in addition to "Davenport Blues," there was another tune

written

by La Rocca and Shields of the ODJB, called "Toddlin' Blues." The

Gennett

file card lists two additional tunes that were recorded but unreleased.

The first was "Magic Blues." No composer is credited so it may have

been

another Beiderbecke original (or maybe the on-the-spot composition

Hoagy

Carmichael recalled) which perhaps could provided us with another rare

glimpse of Bix playing a 12-bar blues. The other was a pop tune

entitled

"No One Knows What's It All About" written by Harry Woods. It had been

recorded by the Memphis Five and the Varsity Eight in a version that

features

Adrian Rollini. Paul Mertz said that Bix's arrangement included "a

tricky

tempo change in the middle, and by now we were all pretty well

lubricated

and kept muffing the tempo change. We never really got it right."

What is interesting to me is that

this session represents the only time Bix attempted to record a jazz

tune

of his own composition. There would be many opportunities to record

more

with Trumbauer or under his own name but he declined. This is

especially

puzzling given the many accounts of Bix sitting at the piano working on

his own music. Laziness or lack of discipline don't explain Bix's

disinterest

in this area. I think it had more to do with Bix's ambivalent feelings

toward jazz.

Davenport Blues is a number composed by Bix Beiderbecke

and recorded by him, with his Rhythm Jugglers, in 1926 (top photo).

With him were Don Murray on clarinet and Tommy Dorsey

on trombone. It is very badly recorded, pre-electric, muddy and

muffled. Only Bix’s cornet emerges with any clarity. Davenport Blues is

not a real blues. It is a jaunty, medium tempo number which in Bix’s

recording consist of 3 sections, each of 32 bars. The first section is

the verse; the melody here has a preliminary unfinished quality about

it as if leading to another more striking one. The second section

consists of a 16 bar variation on the verse theme, followed by a

reprise of the theme itself. The third section is the chorus, the most

distinctive, bitter sweet melody starting with two four note rising

arpeggios, then descending to “blue” Aflat and a trill, followed by a

repeat, a variation and a reprise. Bix’s cornet is tender and relaxed;

he plays very much “on the beat” giving it, to our ears, a rather

archaic quality.

This archaic quality is even more apparent in the version recorded a

year later by Red Nicholls.

If Bix plays on the beat, Nicholls is nailed to it. It is however a

much clearer electric recording and we get a true idea of Nicholls’s

clipped cornet and Miff Mole’s effortful trombone. The tempo

is similar to Bix’s recording. The order is reversed. The chorus is

played first on cornet. The verse comes in with Mole’s trombone before

reprise of the chorus on alto sax, piano and cornet in that order. It

is well drilled and clean but to our ears, even more so than Bix’s, it

is corny – on the beat, jerky and ragged.

Bunny Berigan,

dubbed Bix’s successor in the 1930s by virtue of the lyrical quality of

his playing, also recorded Davenport Blues with his own band in 1938.

Rhythmically and musically this is more sophisticated. Sixteen bars of

the verse from the band are followed by the chorus melody on Berigan’s

trumpet, much better played and with more subtlety than either Bix or

Nicholls. Berigan’s rather more Louis Armstrong like tone gives it more

drama and depth.

Louis Armstrong, recently deceased, was the

subject of a memorial concert at the Queen Elizabeth Hall, London, in

November 1971. On that night Davenport Blues was played as a duet by Alex

Welsh (lower photo above) on cornet and Fred Hunt on

piano. A CD

of

Alex Welsh’s contribution to the concert has been issued (but it is

hard to get). This time it is slowed right down, concentrating solely

on the chorus. Welsh’s entry after an opening piano flourish from Hunt

is stately. The theme is played simply with some flourishes but never

straying far from the melody. At this tempo the melody opens out, and

seems more like a real blues than it is. Welsh’s cornet is clean; it

has something of Bix’s bell like tone but with a burnished quality that

gives it more warmth. Welsh plays the “blue” Csharps and Aflats with

relish, leaning on and roughening them. He gives the melody weight,

drama and pathos.

Hunt’s solo starts with broad sweeping

arpeggios interrupted by a brief boogie passage. The florid right hand

gives way to single note flurries, a section in double time with stride

like piano towards the end. Then Welsh returns. He plays an inversion

of the melody, with interpolations of real blues inflections before

coming back to the melody and some double time interplay with Hunt’s

piano. In the second sixteen bars he stays close to the melody, with

grace notes over double time, then to the last four bars played simply

and straight to a gentle close in slower time. At the end is Hunt's

poignant reprise of the opening notes of the melody high up over

Welsh’s long held final low note on cornet.

There are other

versions of Davenport Blues. But there is no doubt that the version

played by Alex Welsh and Fred Hunt at the Queen Elizabeth Hall on 28

November 1971 in honour of Louis Armstrong is the finest ever recorded.

I am indebted to Hans Eekhoff

for generously sending me the images

of the record labels, of the Gennett file card and of the photograph of

the Rhythm Jugglers, to Randy Sandke for kindly giving me permission to

transcribe the discussion of Davenport Blues from

his booklet "Bix Beiderbecke:

Observing a Genius at Work", and to Rickey Bauchelle for the gift of a

copy of the letter from Tommy Dorsey and for her friendly help.

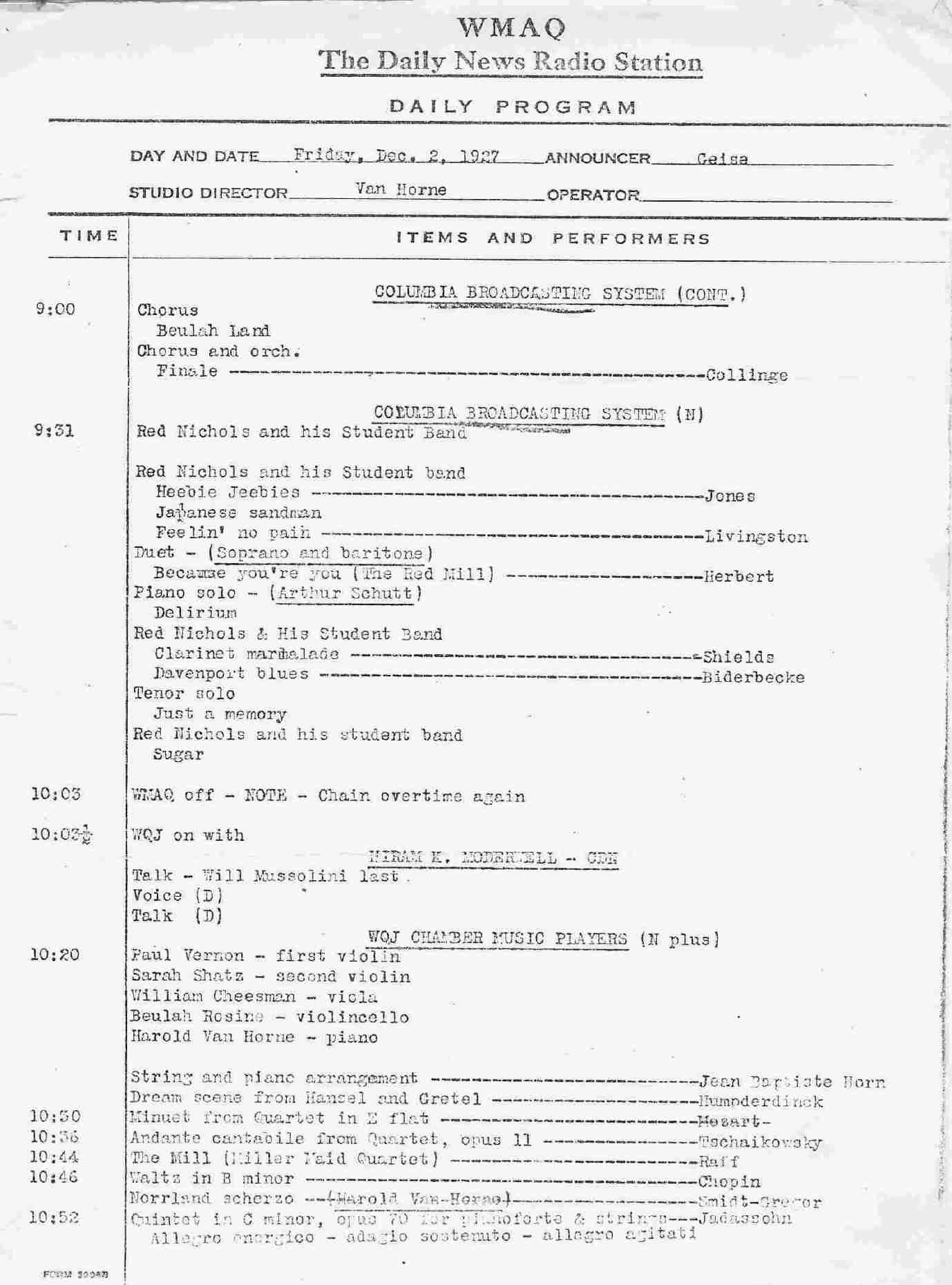

From

http://www.scottchilders.com/timecapsule/TCWMAQ.htm

WMAQ Radio. 1922-2000.

"In 1922,

The Chicago Daily News kicked around the idea of adding a section to

the

newspaper devoted to the new medium - radio. After the new section ran

for

awhile, newspaper execs realized that instead of promoting other

stations, they’d

be better off with their own facility. This was no doubt due to the

fact that

their rival, the Chicago Tribune had been experimenting with radio by

airing an

hour of news on Westinghouse’s KYW. (By 1924, the Tribune purchased

WDAP

and WJAZ, which were merged to become WGN “World’s Greatest Newspaper.”)

A joint venture was formed between the Daily News and the Fair

Department Store.

The Daily News appointed William Hedges station manager. Then, Walter

Strong,

the paper’s managing editor hired Judith Waller away from the

advertising

agency J. Walter Thompson. Waller was appointed the new stations

program

director, announcer and talent scout. She had absolutely no radio

experience!

Despite this, WGU Radio signed on the air on April 13, 1922. After only

a few

days of broadcasting with some clunky old leftover transmitting

equipment, the

station was taken off the air and retrofitted with a new 500 watt

transmitter

and antenna system, located atop the Fair Store. The station finally

signed back

on in October. Upon the inauguration of the new transmitter, Secretary

of

Commerce Herbert Hoover changed the station’s call letters to WMAQ. The

calls

originally had no meaning, but went on to form the motto: We

Must

Ask Questions. By 1923, the Daily News

purchased the

Fair Store’s interest in the station and moved WMAQ to the LaSalle

Hotel. WMAQ

originally shared their broadcast frequency with another radio station

- WQJ.

This was common practice in the early days of radio. In 1927, the

newspaper purchased WQJ and WMAQ assumed the entire broadcast day on

670 kHz. The

station later moved in with the newspaper at the Daily News Building on

Madison

and Clinton in the West Loop in 1929. In

addition to providing musical selections, WMAQ also aired educational

lectures,

household features from the Daily News, children’s programming and was

a

pioneer in radio sports."

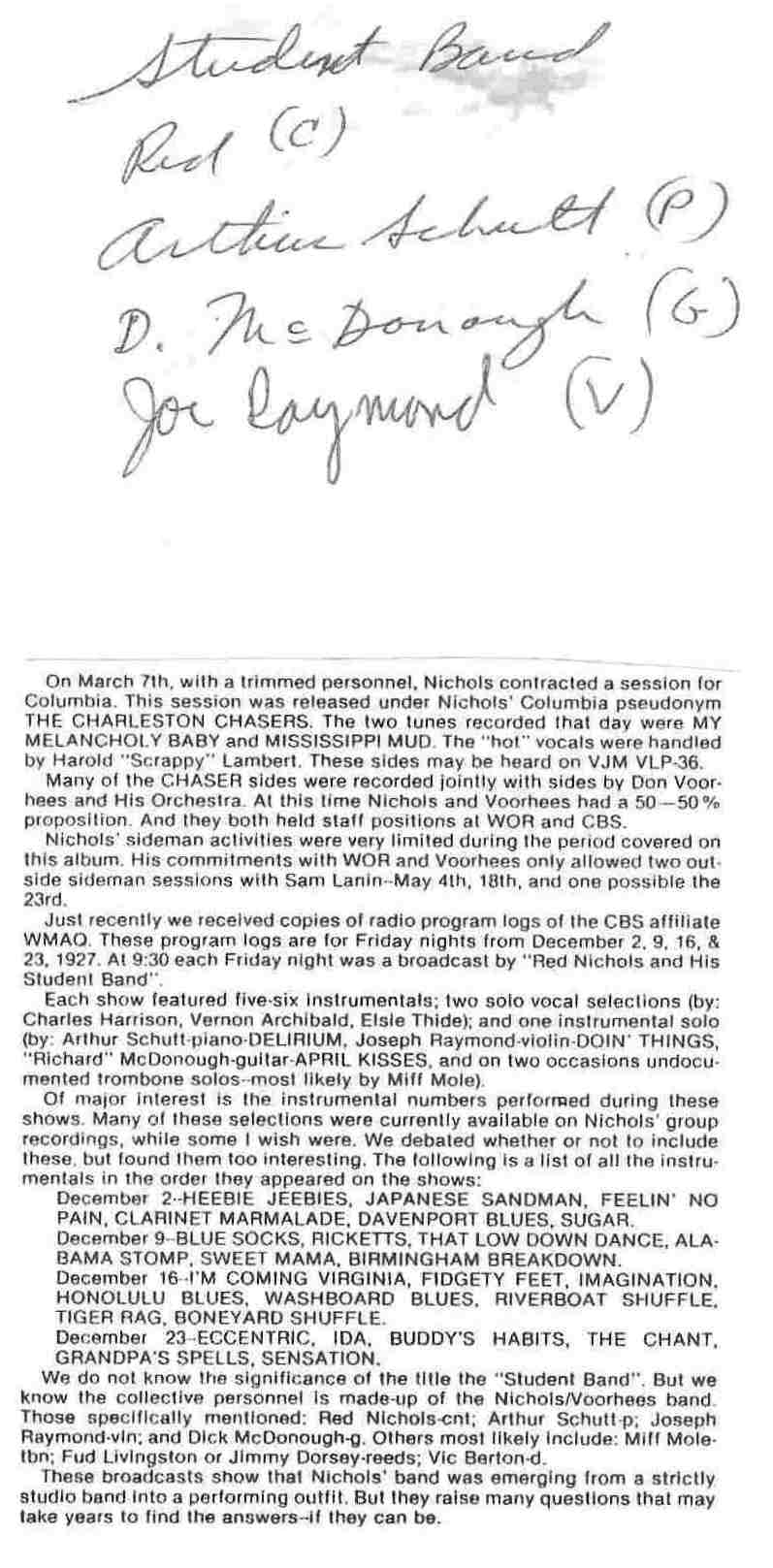

Beginning Sunday afternoon September 18, the competitive element in nation-wide broadcasting enters by way of the 16 carefully selected high powered radio stations included in the Columbia Broadcasting System's network, which covers the United States east of the Rocky Mountains.

In spite of the fact that this is still a day of pioneering in

Radio,

the new Columbia chain enters as a lusty full strided youth, and a well

manned organization, and a wealth of musical and entertainment

experience

as a background.

Don Voorhees, who has the record for the longest unbroken orchestra run on Broadway, and who has been musical director for Earl Carroll since the second edition of the Earl Carroll Vanities, has been put in charge of a dance and specialty orchestra.

Red Nichols, popular for his phonograph record and Radio work, heads a specialty musical group.

Chamber music groups, a string quartet, and several dance orchestra units are included in a list that already totals 80 musicians and groups under exclusive contract.

The signing of these artists and organizations represents an innovation in the field of nationwide radio broadcasting as a result of the Columbia chain's policy, which sells not only the chain over which the program is broadcast but also the program itself, together with an adequate staff of Radio showmen, continuity writers, directors and technical experts, to insure that the programs will justify the slogan which the Columbia chain has set for itself. The slogan is: "Always entertainment on every Columbia hour.

Major J. Andrew White, dean of broadcasters and builder of the first

Radio station designed to furnish free entertainment to Radio set

owners,

as Vice-President of the Columbia chain brings to the Columbia network

an

experience dating back into Radio's very earliest days, and brings also

his pioneering spirit which has in the past been responsible for so

many

of the forms of Radio entertainment so popular today.

Work has progressed to the finishing stages in the three new indoor and two outdoor studios for WOR, which is the key station to be used by the new Columbia chain. [Note -- these studios were still uncompleted at the time of the initial CBS broadcast, and in fact network master control ran from a makeshift control facility set up in the WOR men's room.]

No announcement as to the sponsors of the programs have yet been

made,

except in the case of the Columbia Phonograph company, which will have

the hour between 9 and 10 o'clock each Wednesday evening.